The last decade has seen some pretty big changes to the workday landscape. Increasing competition for sales, jobs, and talent is quickly making the Monday through Friday, 9 to 5 work week a nostalgic memory. As technology makes coming in to the office less and less necessary, work and leisure time have become more and more integrated. Constant connectivity means many employees can work from the comfort of their homes – or their favourite resort – but for many this also means that work is always with them, even when they are supposed to be on holiday, days that were once reserved for relaxation and family time.

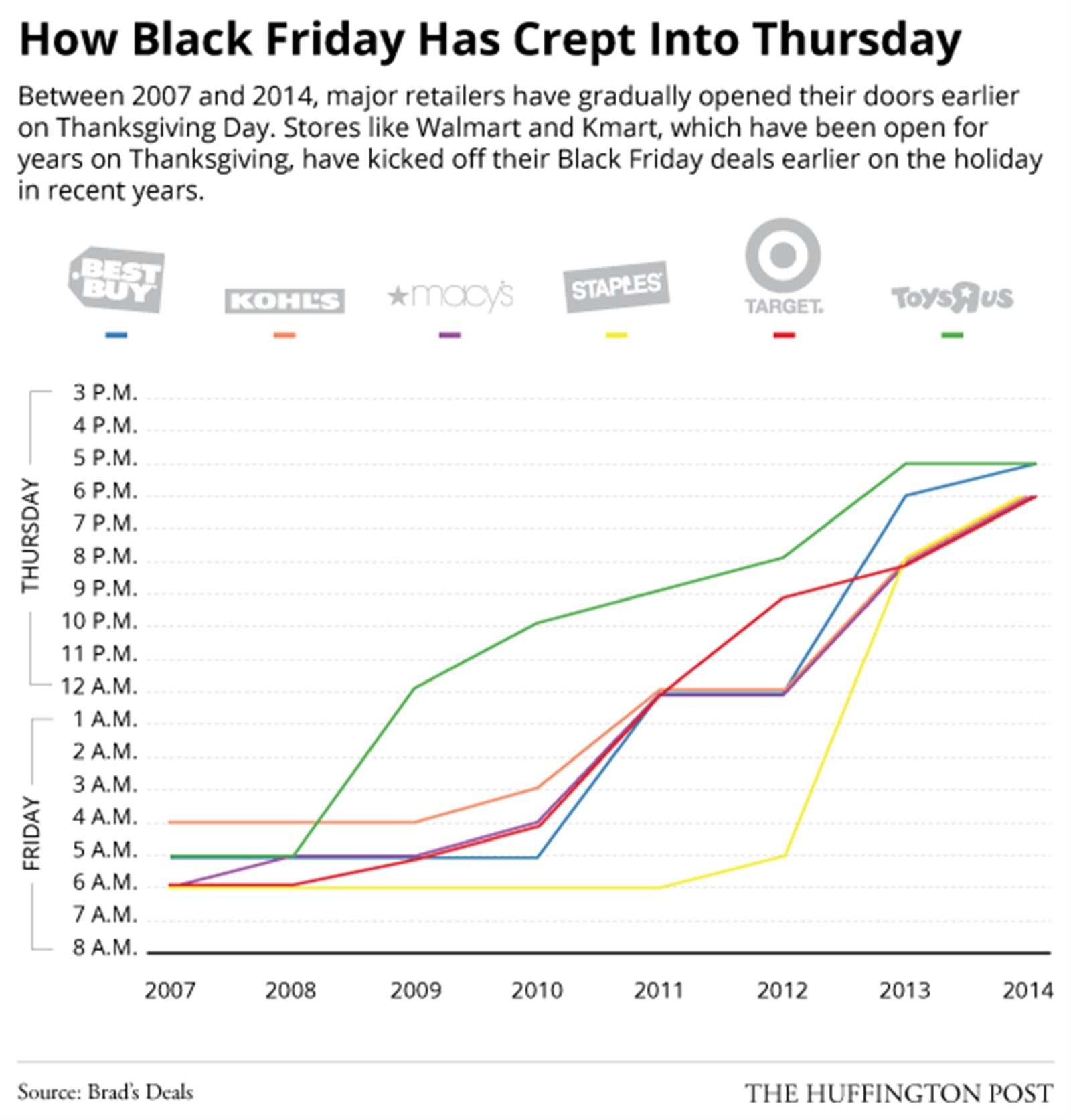

A decidedly global market means there are deals to be made and processes to manage 24/7, 365 days a year. In this competitive economy, holidays be a great opportunity to get ahead while competitors take time off. Nowhere is this truer than in the retail sector where, at least in the United States, holiday family time is quickly turning into holiday shopping time as competition drives stores to open earlier and stay open longer in order to entice shoppers to jump on seasonal deals. Retail workers, then, are called on more and more to spend their holidays at work so that the companies they work for can get ahead of the holiday selling game.

Meanwhile, progressive companies, recognising the role of work-life balance in increasing and maintaining productivity, are offering more and more time off and getting very creative in their efforts to ensure that employees use it. Employers are turning to everything from vacation bonuses to mandatory leave to persuade their workers to take the time off afforded them by generous company policies. Despite their efforts, though, many office workers, still reeling from the job insecurity of the recent recession, feel uncomfortable taking time off, fearing that they will fall behind or that their willingness to be away from work might be interpreted as a lack of commitment or drive.

The result? American workers, whether by choice or by force, are working more hours a day, more hours per week, and more hours each year than they used to. Many of those extra hours will be worked on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day - federal holidays that once turned every American shopping centre into a ghost town for a day. With these holidays fast approaching, we start to wonder - should American workers get ready to say "good-bye" to holidays off from work?

Only in America

The United States is, notoriously, the only country with an advanced economy that does not require employers to provide paid time off. In Europe, the EU Working Time Directive requires Member States to "take measures to ensure that workers enjoy:

- the minimum daily rest period of 11 consecutive hours per period of 24 hours;

- the minimum period of one rest day on average immediately following the daily rest period in every seven-day period;

- for a daily period of work of more than six hours, a break as defined by the provisions of collective agreements, agreements concluded between social partners or national legislation;

- not less than four weeks' annual paid holiday, qualification for which shall be determined by reference to national practice/legislation;

- an average weekly working period of not more than 48 hours, including the overtime for each seven-day period."

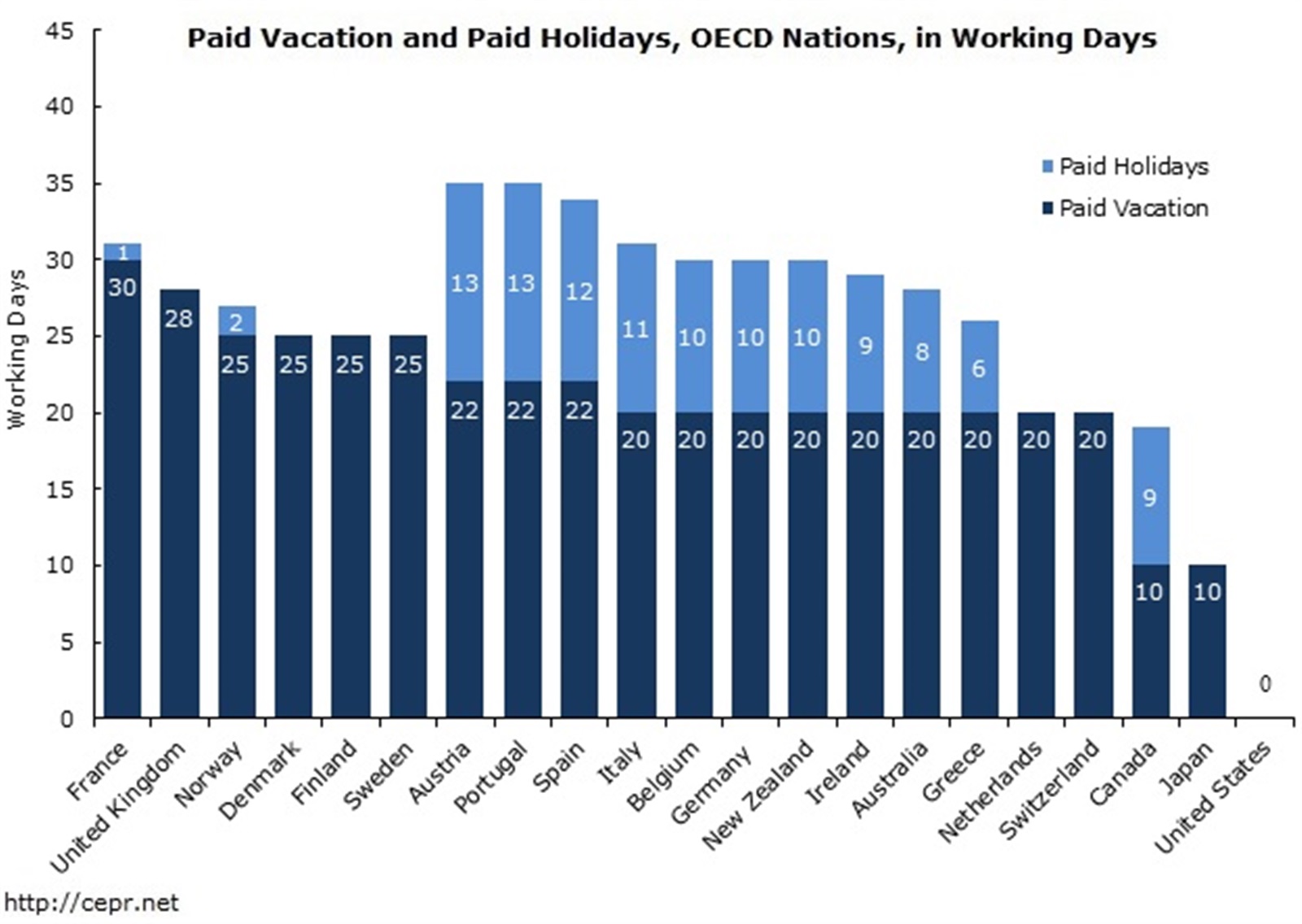

Many European and non-EU countries provide even more leisure time to their workers. Finland, Brazil and France, for example, each guarantee what adds up to 6 weeks of paid time off to full-time workers. But in the U.S., paid time off is considered part of an employee’s benefits package, and it is entirely up to the employer whether or not to offer any at all. In order to compete for the best talent, many businesses that require skilled workers offer packages that include paid time off, but aside from the most competitive, very few compare to those offered in other countries, averaging only about 10-15 work days off each year, plus a smattering (6 on average) of federal holidays. In 2014, about 25% of U.S. employees were without any paid time off at all.

This table from the popular publication "No Vacation Nation" from the Center for Economic and Policy Research illustrates how the U.S. compares (or fails to) with other advanced economies when it comes to guaranteed paid time off. Days per year are based on a full-time work week, which ranges from 35-48 hours, depending on the country.

Federal holidays in the United States

Official federal holidays in the United States, then, are not mandatory days off for all, or even most, U.S. workers. Only employees of non-essential offices of the Federal Government are entitled by law to have these days off. While state governments often follow suit, not all states recognize every Federal holiday, and only a handful of them require businesses to give employees any of these days off during the year.

These U.S. Government holidays are only guaranteed� days off for non-essential government offices:

- New Year's Day (January 1)

- Birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr. (Third Monday in January)

- Washington's Birthday (Third Monday in February)

- Memorial Day (Last Monday in May)

- Independence Day (July 4)

- Labor Day (First Monday in September)

- Columbus Day (Second Monday in October)

- Veterans Day (November 11)

- Thanksgiving Day (Fourth Thursday in November)

- Christmas Day (December 25)

Because federal offices are closed on these days, most banks and bond markets (which trade in U.S. government debt) are also closed, and most offices in the U.S. (93-97%, depending on the holiday) close on these days as well. In the past, this was, to some extent, because postal mail and other communication services would be closed on those days, along with the banks, which made it difficult to conduct business anyhow. The advent of email and other 24/7 services, online banking and transactions that can be carried out at any time have made closing on these days more of a tradition now than a requirement for businesses, and some are starting to take advantage of those days to get ahead of the market and to conduct business with partners and customers in other countries where work is proceeding as normal.

Forced to work holidays

According to a Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data, retail companies typically boost payrolls by 3-4% during the holiday season (from October to December). Many of those hired during this time accept these temporary positions knowing that they will be expected to work on through the holidays. However, year-round workers are also finding more and more that holiday hours that used to be voluntary are becoming mandatory. In 2014, 25% of U.S. workers expected to work on Thanksgiving, Christmas, or New Year’s Day, or a combination thereof. An Allstate/National Journal Heartland Monitor poll that year showed that, of those who were likely to work one or more of these holidays, about 55% had little to no choice in the matter.

In the Unites States, federal law does not currently require employers to provide any extra compensation to employees made to work on a holiday. Though some companies in the service industry, including many airlines and hotel chains, offer incentives to office workers manning their customer service and reservation lines on these days, for many workers on the ground, especially in hospitality and retail, these days are just another day in their weekly schedule.

Since the U.S. Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) only requires employers to pay for time worked, employees who chose to take the holidays off to spend time with family or travel are not entitled to pay during that time unless paid time off is part of their benefits package and time off during the period is approved. In companies that operate 365 days a year, time off during the busy holiday season is most often is dependent on seniority. At present, though, only about half of America’s lowest wage earners receive any paid vacation anyway, so a large portion of those at the lowest end of a company’s pay scale simply cannot afford to take time off.

Beyond not being able to afford time off without pay, many workers in the retail sector face unemployment if they do not agree to make themselves available to work on the holidays. As store openings encompass more and more days like Thanksgiving and New Year’s Day, on which almost all businesses would have been closed 15 or 20 years ago, a larger and larger share of American workers are included among those working the holidays.

This graph from Huffington Post illustrates how this trend has affected Thanksgiving hours.

While this trend would seem to suggest that American workers, especially those in the lowest-wage earning percentage, should get ready to kiss the holidays good-bye, state legislation is starting to close the gap that federal regulation leaves open. Massachusetts, Maine, and Rhode Island already have laws banning most stores from opening on Thanksgiving and Christmas and several other states, including California and Ohio have seen a push by certain lawmakers to enact legislation benefiting workers asked to work on the holidays. At the federal level, Senator and Democratic Presidential hopeful Bernie Sanders has proposed federal legislation that would require employers to provide at least 10 days of paid vacation to every full-time employee, bringing the issue of paid leave - and potentially holiday time off - to the national presidential stage.

Choosing to work holidays

So what about the 75% of working Americans who do receive paid time off? A 2011 Reuters/Ipsos poll found that some 43% of U.S. workers fail to use all of the vacation time allotted to them each year. A similar survey conducted by Glassdoor.com found that the average employee takes only half of what is allotted, and 15% don’t take any vacation time at all. And this is not a phenomenon confined to the vacation-stingy United States. A recent YouGov survey showed that about a third of full-time workers in the U.K. failed to use the 28 days allotted to them by law.

So if retail workers are working the holidays because they have to, are salaried workers working the holidays because they want to? Well, not exactly.

In recent years, a number of theories have been developed to try to explain why modern workers are so determined to overwork. The most cheerful of these is that people just enjoy their jobs more. It is the case that a larger percentage of salaried employees these days are college-educated and, in many cases, have chosen their career paths out of some affinity for a particular line of work or interest in a certain subject. This theory suggests that, for example, a computer programmer or a graphic designer might be spending more time at work because they simply enjoy what they do and want to do more of it.

While this is sure to be the case for certain individuals, with employee engagement averaging about 14% around the world, it is a bit naive to suppose that the majority of today’s workforce spends more time at work because they find their jobs as enjoyable as their leisure time. An alternative theory, and one to which much of the labour force, from clerks to CEOs, can relate, is the reality that, even for those who aren’t paid hourly, time adds up to money. Indeed, the more one gets paid for one’s work, the more valuable that work seems to feel and the more of it seems to need doing. Add to this the pressures of a competitive job market or the still-fresh memory of rounds of lay-offs necessitated by the too-recent economic downturn, and the impulse to fill one’s time with work becomes easy to understand.

Closely connected to this state of affairs is the turnaround of the 20th century that saw hard working businessmen take the place of inheriting men of leisure as the upper class elite, especially in the United States where almost every wealthy family had earned their money through some enterprise. Especially in the executive suite, the more precious one’s time is, the more important - and indispensable - one is perceived to be. Staying in the office on Christmas or New Year’s, then, says to others "my work is too important to wait another day and I am the one to do it."

Pretending not to work on holidays

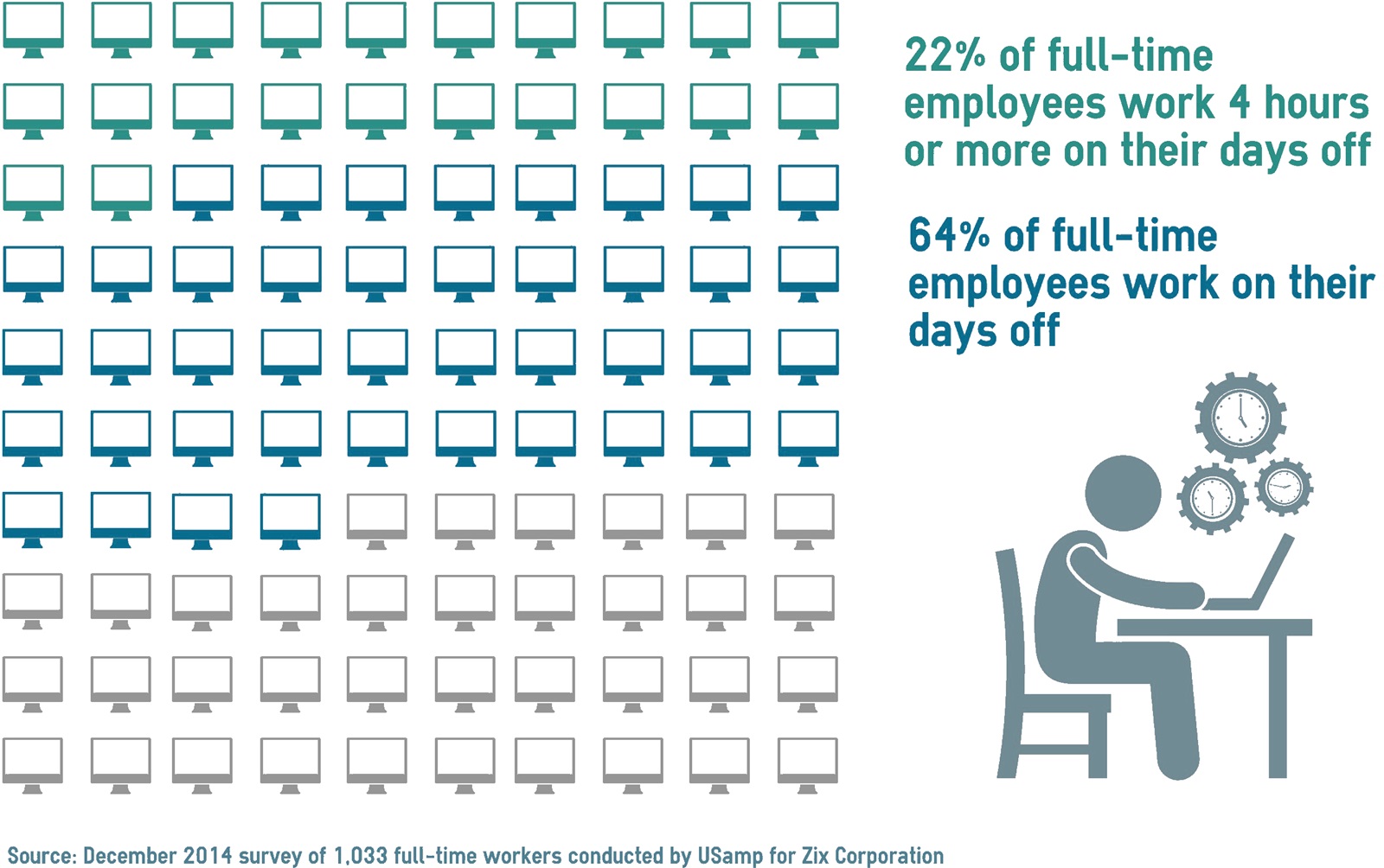

Right there with those who choose to work through the holidays are those who, while they may not be in the office, will indeed be doing work during their time off. A 2013 poll by the Pew Research Center indicated that, even among those who were not technically going to be at work during the holidays, 42% expected to check their work email while away, and more than half of those planned to check in at least once a day.

The survey highlighted a trend toward working away from work, noting that the younger generations are the most prone to this habit. 51% of respondents under 35 said they would be checking in compared to 40% their older colleagues, who prefer to catch up when they return to the office. A survey of full-time working professionals conducted in December of the following year by USamp for Zix Corporation indicated that 57% of respondents intended to do some work during their holiday break.

This all-day, every day work schedule is becoming commonplace all over the world. In much of Europe, it is viewed as a problem, with solutions ranging from German carmaker Volkswagen’s decision to block its servers from distributing emails outside of working hours to France’s resolution last year that people working in certain fields be prohibited from checking work emails or answering work calls outside of the country’s mandated 35-hour work week.

Whether it’s to keep ends meeting or to achieve a prestigious end, people are working more and taking less leisure than they used to. In the United States, the previously sacrosanct practice of holiday closures for any business not deemed absolutely necessary to well-being of the people is certainly falling by the wayside as commerce becomes a ‘round the clock activity and technology enables business to be conducted anytime and anywhere. But the holiday has not yet been surrendered. The understanding that time off is as important to productivity as commitment and skill is starting to push back against the image of the always-busy worker bee. The value of relationships as a driving force in society is starting to stem the onrushing tide of consumerism. It remains to be seen what the balance will look like as work and leisure time continue to blend together, the diversity of days held holy continues broaden, and the question of worker’s rights continues to be debated, as it has been for centuries.